A Creature of Its Time: The Pension Bureau

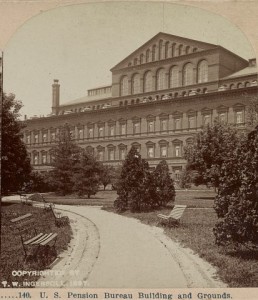

It was an unimpressive start. In the early years of the nineteenth century, only a handful of War Department clerks reviewed pension applications by Revolutionary War veterans and widows. By the century’s end, United States’ pension administration would grow into the largest division in the Interior Department. Headed by an appointed commissioner and occupying an imposing building, it employed more than 1,700 men and women, overseeing the distribution of $138 million in pensions to nearly a million Union veterans and surviving relatives.

The sheer size of the Union army in the American Civil War caused much of this transformation, but Congress further amplified it with far-reaching changes. Lawmakers added pensions for surviving dependents beyond the customary payments to widows. Lawmakers went as far as defining targeted benefits, such as $25 per month for the loss of both eyes and $20 for both feet. In 1879 Congress allowed disability payments retroactive to a soldier’s discharge; in 1890 it authorized pensions for conditions originating after the war; and in 1907 all veterans sixty-two or older became pensionable.

The Pension Bureau found itself with a burden and an opportunity. A total of 325 veterans and widows had applied for new pensions in 1860. More than 75,000 applications arrived in 1865, and the annual average remained above 70,000 for the rest of the century. This caseload forced the Bureau to lead the way in institutional development.

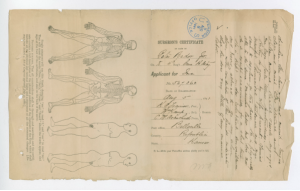

It seized the opportunity by devising a standard procedure to determine benefits. Typically aided by a claim agent (an attorney or other entrepreneur who assisted applicants for a fee), prospective pensioners filed a declaration of their qualifications. Pension Bureau examiners then contacted the War Department for evidence of service and any medical treatment. Officials next notified veterans to report for a physical examination; survivors were typically asked to produce evidence such as the veteran’s death certificate and proof of their relationship. The Bureau appointed local physicians for medical examinations, organized into three-member boards by the 1880s. The examination was the heart of the application, meant to produce “a full symptom-picture of each case.”[1] The physicians returned their assessment to the Bureau, whose medical referee and board of review rendered a pension award or rejection. The 1907 revision lessened the need for medical examinations, but the outlines of the process remained throughout the existence of the pension system.

Bureau leaders made other attempts to increase administrative control over pensions. An early commissioner established a medical division “to correct and adjust all medical questions” about local examinations.[2] The Bureau promoted accountability through a special examination division, which investigated pension claims of questionable validity. In the 1870s, a commissioner proposed to eliminate local medical examiners because they were “neighborhood practitioner[s], whose professional interest it is to please the claimant at the expense of the Government.”[3] If Congress approved, sixty full-time government surgeons would be needed to conduct impartial examinations.

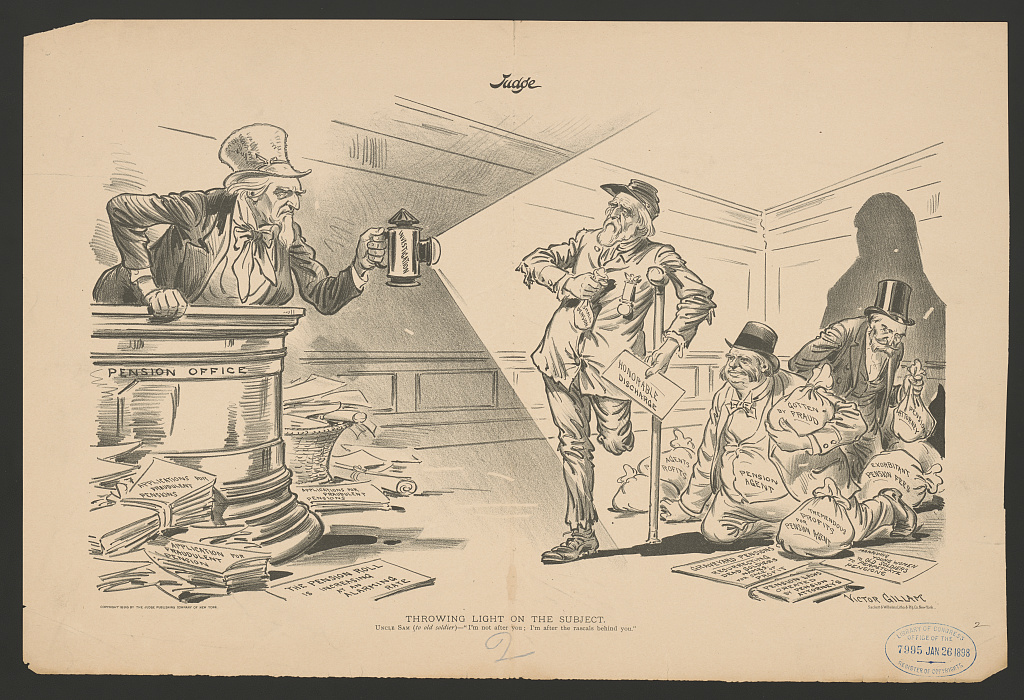

Attempts to put the Pension Bureau “upon a thorough business basis” were overwhelmed by powerful forces pulling in other directions.[4] Chief among these was the presumption that government benefits enticed the recipients of those services to vote for their benefactors. Republicans, the party of Lincoln and typically the party in power, found it easier to claim the role of benefactor, but both parties got into the act.

The Republicans also enjoyed an intricate alliance with claim agents and the Grand Army of the Republic, the largest organization of Union veterans. The best-known exploitation of this alliance was by James Tanner, a former GAR official and future claim agent who became pension commissioner in 1889. Tanner promised “a pension for every veteran who needs one” and delivered a fifty percent increase in new awards during his brief tenure.[5]

The Bureau’s policies to exert more control were also vulnerable to misuse. Instead of using special examiners to investigate fraud, a commissioner brought scores of them to Ohio in 1884, where they reportedly urged veterans to vote Republican “with the express understanding that their pensions would be withheld in case they did otherwise.”[6] Instead of implementing the “sixty-surgeon” plan, lawmakers sided with George Lemon, a newspaper publisher, claim agent, and unofficial GAR spokesman. Lemon warned that the sixty-surgeon plan aimed “to centralize the whole system here at Washington; to escape the wholesome effect of neighborhood watchfulness, and to establish petty tribunals of unlimited power and unlimited arrogance.”[7] The proposal died in Congress.

Other forces also eroded the Bureau’s effectiveness. A recent study argued that local examining physicians were moved by more than empathy toward applicants: generous recommendations ensured future examination fees when pensioners sought increases.[8] Another study found racial and ethnic prejudice in pension decisions. Local physicians rejected more African-American veterans than whites; officials in Washington added their own discrimination against black applicants, and they developed a bias against the “downtrodden races” of southern and eastern Europe.[9]

Suspended between inclusion—with the ever-widening definitions of benefit worthiness—and exclusion—the restriction of benefits to veterans not afflicted with “vicious habits”—the Pension Bureau never developed a coherent approach to its mission. It was hardly alone: Gilded Age agencies had little appetite or ability for defining federal policy. Bureaucratic empowerment would come from Progressive activism after the turn of the century. In the meantime, Civil War veterans remained a population to be reckoned with and the Bureau remained a creature of its time.

One Civil War pension is still being paid today.

About the Authors

Larry Logue is a senior fellow at the Burton Blatt Institute at Syracuse University. Peter Blanck is chairman of the Burton Blatt Institute and University Professor at Syracuse University. In addition to numerous works on Civil War veterans and public policy, they are co-authors of Heavy Laden: Union Veterans, Psychological Illness, and Suicide (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming).

Footnotes

[1] U.S. Pension Office, “Instructions to Examining Surgeons,” Aug. 1, 1884, p. 9.

[2] Report of the Commissioner of Pensions [1871], House Exec. Doc. 1, 42nd Cong., 2nd sess., p. 388.

[3] Report of the Commissioner of Pensions [1876], House Exec. Doc. 1, 44th Cong., 2nd sess., p. 701.

[4] Report of the Commissioner of Pensions [1890], House Exec. Doc. 1, 51st Cong., 2nd sess., p. 16.

[5] James Marten, American’s Corporal: James Tanner in War and Peace (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2014), 107. Increase calculated from Report of the Commissioner of Pensions [1889], House Exec. Doc. 1, 51st Cong., 1st sess., p. 438; Report of the Commissioner of Pensions [1890], House Exec. Doc. 1, 51st Cong., 2nd sess., p. 42.

[6] John William Oliver, “History of the Civil War Military Pensions, 1861-1885,” Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin 4 (1917), 112.

[7] “The Commissioner’s Bill,” National Tribune, Feb. 1, 1878.

[8] Nicholas R. Parrillo, Against the Profit Motive: The Salary Revolution in American Government, 1780-1940 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 145-155.

[9] Larry M. Logue and Peter Blanck, Race, Ethnicity, and Disability: Veterans and Benefits in Post-Civil War America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 56-73, 97-109.

Further Reading

Peter Blanck, “Civil War Pensions and Disabilities,” Ohio State Law Journal 62(2001), 109-238.

Peter Blanck and Michael Millender, “Before Disability Civil Rights: Civil War Pensions and the Politics of Disability in America,” Alabama Law Review 52 (2000), 1-50.

Peter Blanck and Chen Song, “Civil War Pension Attorneys and Disability Politics,” Journal of Law Reform 35 (2002), 137-217.

Daniel P. Carpenter, The Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputations, Networks, and Policy Innovation in Executive Agencies, 1862-1928 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001).

William H. Glasson, Federal Military Pensions in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1918).

Jerry L. Mashaw, Creating the Administrative Constitution: The Lost One Hundred Years of American Administrative Law (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2012).

Theda Skocpol, Protecting Soldiers and Mothers: The Political Origins of Social Policy in the United States (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992).

Tags: Civil War, Disability History, Larry Logue, Pension Bureau, Pension Office, Peter Blanck, Reconstruction, Veterans History Posted in: Uncategorized