“No One Knows What to Do” – Clara Barton and the Lincoln Assassination

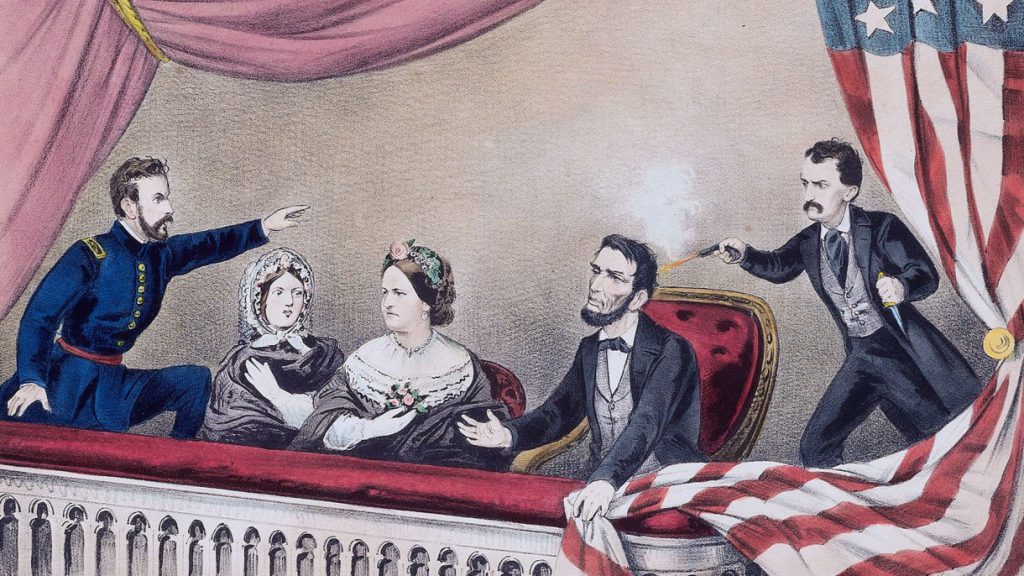

On a foggy night in April 1865, Clara Barton trudged home through the muddy streets of Washington. The Union capital still basked in the glow of victory on that Good Friday. Just days before, the city celebrated the defeat of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army at Appomattox Court House. As she neared her home, an astonishing and unbelievable rumor raced up the street: President Abraham Lincoln had been shot at Ford’s Theatre, just blocks away from Barton’s rented room.

On one of the most momentous nights in American history, Clara Barton was witness to a nation passing from exultation into mourning in a matter of moments. Once she heard the frightful news from Ford’s Theatre, it is unclear where Barton went or what she did, but certainly, sleep must have been difficult on the evening of April 14, 1865.

Who had committed such a treacherous act? What did this mean for the ongoing war? Was this an act of war by Confederates on the retreat? What would it mean for life after the war?

Lithograph of the Lincoln Assassination at Ford’s Theater

As dawn broke the next day, the citizens of Washington waited for news of Lincoln’s condition. For a sleepless city, the news struck like a hammer blow. President Abraham Lincoln died from a gunshot wound to the back of his head at 7:22 a.m., April 15, 1865.

Barton’s simple diary entry from that mournful day mirrors those experienced by Americans after countless tragedies in the century and a half since the Lincoln assassination.

President Lincoln died at 7 o’clock this morning

The whole city in gloom

No one knows what to do…

Vice President John[son] inaugurated President

The passage “no one knows what to do” is particularly poignant. It elicits memories of events from our own lives; the horrific days that we mark each passing year: December 7, November 23, September 11. Barton, the people of Washington, and eventually the entire Union, felt the blow as the news spread by telegraph, newspaper, and word-of-mouth. It was not simply an attack on Lincoln, but a plot against the entirety of the United States Government carried out by John Wilkes Booth and his fellow conspirators. Secretary of State William Seward had been savagely attacked in his home by a knife-wielding assailant and Vice President Andrew Johnson had only been saved when his assailant grew unnerved and failed to carry out his part in the plot.

Barton’s brief diary entries in the mournful days that followed the Lincoln assassination illustrate the chaos and horror left behind in the wake of the events of April 14, 1865.

Sunday, April 16, 1865.

Assassins not detected.

Known to be J Wilks Booth,

The attempted Murder of Mr

Seward & family was sup-

posed to be by one Surrat-

I was quiet all day.

Monday, April 17, 1865.

Attempted to find some help –

Went to Surg Genl office

Could get no one.

The President embalmed &

preparing to be laid in state

Tomorrow,

Mailed 100 letters. –

Tuesday, April 18, 1865.

President Lincoln laid in

State – Depts went in bodies

To see him. Resolutions passed

at the Mass rooms in

honor of the President…

Heard this evening that

The assassin of Mr Seward

had been arrested at 2 o clock this morning

– dressed as a laborer, on I-E St.

Borrowed some tables to write on –

Wednesday, April 19, 1865.

Funeral of President Lincoln

I remained in doors all day –

Thursday, April 20, 1865.

President lain in state

At the capitol

Sally & Fannie & Vester

returned from Mass…

Friday, April 21, 1865.

President Lincolns remains

taken on to Baltimore

great search for Booth.

In the aftermath of the Lincoln assassination, the war-torn nation eventually found its footing. Those responsible for carrying out John Wilkes Booth’s plot were either rounded up or hunted down. Booth himself died amid bullets and flames in a tobacco barn in Virginia. Remaining Confederate armies were gradually surrounded and forced to surrender. General Joseph Johnston surrendered his forces on April 26, bringing about the end of major hostilities, and the final few Confederate forces surrendered during the summer of 1865.

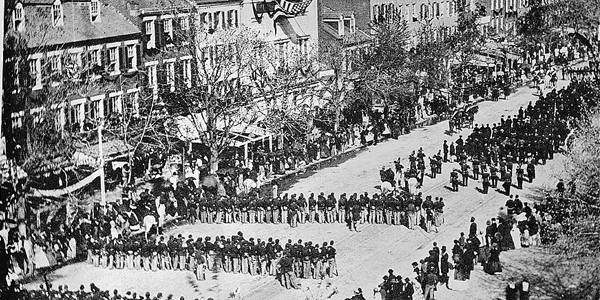

Lincoln’s funeral parade in Washington

As the mourning for the martyred president carried on throughout the North, Clara Barton privately grieved the loss of a man who had recently backed her next major project. In March 1865, Lincoln had thrown his support behind Barton’s effort to search for U.S. personnel who had gone missing during the conflict. In the wake of Lincoln’s assassination, she sought and received approval from his successor, President Johnson to carry on her work. Addressing President Johnson in late May, she wrote:

The undertaking having at its first inception received the cordial and written sanction of our late beloved President, I would most respectfully ask for it the favor of his honored successor.

The work is indeed a large one; but I have a settled confidence that I shall be able to accomplish it. The fate of the unfortunate men failing to appear under the search which I shall institute is likely to remain forever unrevealed…

Her note to President Johnson came with the endorsement of arguably the most popular man in the North – Ulysses S. Grant. “The object being a charitable one, to look up and ascertain the fate of officers and soldiers who have fallen into the hands of the enemy and have never restored to their families and friends,” the general wrote on June 2, 1865, “is one which Government can well aid.”

Gradually, Barton and the nation moved forward into new battles and struggles in the summer of 1865. Barton went on to visit the site of the infamous Andersonville prison and dove into her work at the Missing Soldiers Office. Fights over Reconstruction and the future of the nation after a conflict that claimed more than 620,000 lives captivated and engrossed the American people.

Yet, the memories of April 14-15, 1865 remained raw. “Excitement and gloom,” writes historian Martha Hodes in her book Mourning Lincoln. “Those were the two words people wrote down again, and again” (excite meant to elicit strong emotions of any sort) after the assassination.

With those who lived through the Lincoln assassination, we’ve shared an ordeal. The “excitement and gloom” of an earth-shattering event. Those who remember where they were when they heard the news that John F. Kennedy had been shot, watched as the World Trade Center crumbled on television, or looked across the Potomac River to see smoke rising from the Pentagon endured similar mental and emotional anguish experienced by Clara Barton and others in Washington on April 14, 1865. And with the feelings of sadness and horror came the awareness that, suddenly, everything had changed. The world would never be the same.

About the Author

Jake Wynn is the Program Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, Clara Barton, John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln Assassination Posted in: Uncategorized