Women Who Went to the Front

Clara Barton’s relentless efforts to visit and care for wounded soldiers on the Civil War’s front lines stands as one of her most significant legacies. Barton joined the army in the field during the Battle of Antietam, earning a reputation as the “Angel of the Battlefield.” She also arrived to offer aid at Fredericksburg, Fort Wagner, and long list of other engagements. But in reality, Barton was just one of many women who defied social conventions and rushed to the front to alleviate the suffering of the wounded and dying.

In the early days of the Civil War, military authorities often denied women the opportunity to provide assistance at the front lines. It was a common belief in mid-19th century America that the battlefield – or public life generally – was no place for women of propriety. Those who wished to keep women out of the field of medicine (if they thought women could be capable nurses at all) sought to “protect” their delicate sensibilities from the horrific sights of war and were concerned of the intimate situations they might find themselves in with male patients. The overwhelming numbers of casualties as the war dragged on aided women’s efforts to break down social barriers and allowed women nurses to pitch in.

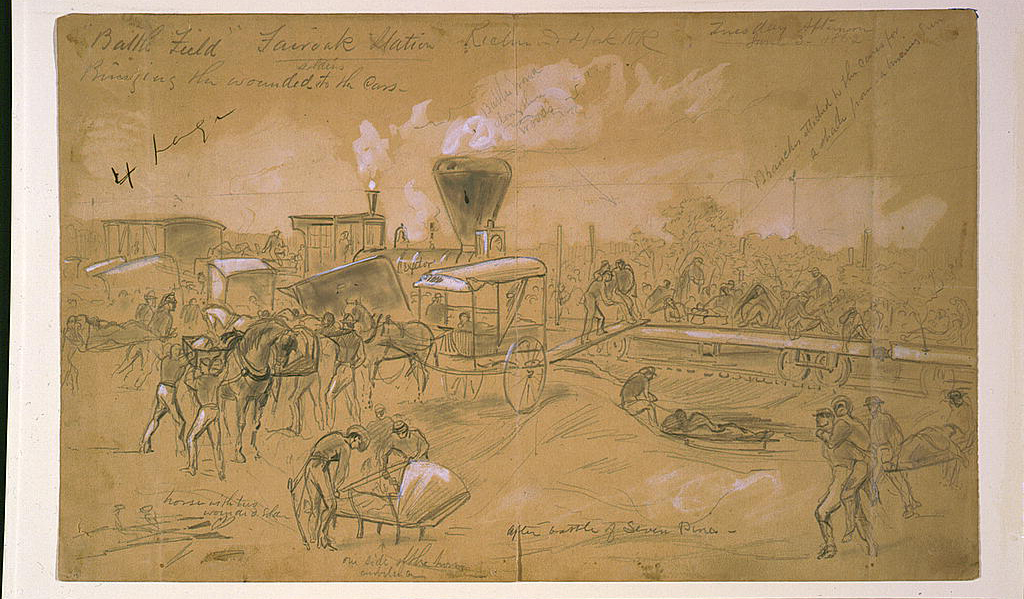

An example from early 1862 occurred when 19-year-old Constance Cary of Virginia met resistance in her attempts to alleviate soldiers’ suffering. She remembered in the aftermath of the Battle of Seven Pines that “up to that time the younger girls had been regarded as superfluities in hospital service.” But the necessities of battle opened an opportunity for Cary: “On Monday two of us found a couple of rooms where fifteen wounded men lay upon pallets around the floor and, on offering our services to the surgeons in charge, were proud to have them accepted.”[1]

Smaller numbers of Southern women left home to serve because the front line often came directly to them. Some, especially in cities like Richmond located near many large battlefields, opened their homes to recovering soldiers. Others, especially in small towns adjacent to battlefields in rural areas, had no choice but to help as larger medical facilities were too far away. Netta Lee’s home in Shepherdstown, Virginia held a recovering Confederate soldier in every available room after the Battle of Antietam in September 1862. Her time among the wounded in her home left a lasting impression on her. She remembered vividly when “I saw my first wounded man, with two soldiers supporting him as the surgeon probed for a ball in his wrist. He asked for water and I ran to get some.”[2] Netta Lee, like many women who had never encountered a wounded soldier before, jumped into action to offer whatever assistance they could despite their shock at the often grisly wounds.

Procuring water, food, medicine, and other supplies for the surgeons became a common task for women whose homes were forcibly converted into hospitals. Others performed the valuable service of spending time with the sick and wounded. With nothing to do but rest, many recuperating soldiers suffered from boredom more than anything else. By talking with them, playing games to pass the time, or writing letters to their families, nurses eased the misery of time spent in a hospital.

For those whose sympathetic spirit moved them closer to the battlefront, the job of caring for the wounded could be deadly. Bullets and shells did not discriminate between soldiers and women relief workers along their trajectories. Clara Barton narrowly avoided death while offering a wounded soldier a drink of water when a bullet went through her sleeve and killed the soldier at the Battle of Antietam. Nurses were occasionally wounded during their service in the field. Juliet Opie Hopkins of Virginia was shot twice in the legs at Seven Pines in 1862. Annie Etheridge of Michigan was shot in the hand at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863, and Elmina Spencer of New York was shot through the sciatic nerve at City Point, VA in 1864. None of these women left the front because of their wounds. While the danger of being wounded was ever present on the battlefield, the more dangerous threat for women at the front, as with soldiers, was disease.[3]

For nurses who spent any amount of time among sick soldiers, disease was impossible to avoid as two thirds of all Civil War deaths resulted from disease rather than battlefield injury. Nursing in a Civil War hospital ward ensured close contact between sick patients and caregivers. Pennsylvanian Clara Jones wrote home of her time in a hospital that “the doctor…assured me that I could not possibly escape” contracting disease while working there.[4] She eventually came down with a case of typhoid fever that spread among her patients. Jones survived her ordeal, but not all were so lucky.

Julia Quigley of Shepherdstown succumbed to scarlet fever while her home was in use as a hospital following the Battle of Antietam. Quigley’s death, and the death of others from disease while caring for sick soldiers demonstrates that by offering their aid, women risked their lives.

Women continued to offer their help in spite of the risks. Those

who commented on their motivations seemed to enjoy being participants in

soldiers’ medical care because it made them feel like they were making a

positive difference with those who needed it. Philadelphian Cornelia Handcock summed

it up best when she wrote from a field hospital near Fredericksburg that “I

never was better in my life: certain I am in my right place.”[5]

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Endnotes

[1] Jane E. Schultz, Women at the Front: Hospital Workers in Civil War America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 17.

[2] Kevin R. Pawlak, Shepherdstown in the Civil War: One Vast Confederate Hospital (Charleston: The History Press, 2015), 61.

[3] Schultz, Women at the Front, 85.

[4] Clara Jones to Mr. Hollingsworth, October 9, 1862.

[5] Schultz, Women at the Front, 108.

About the Author

John Lustrea is a member of the Education Department and the Website Manager at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He earned his Master’s degree in Public History from the University of South Carolina. Lustrea has previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park during the summers of 2013-2016.

Tags: Annie Etheridge, Antietam, Civil War nurses, Clara Barton, Constance Cary, Elmina Spencer, Juliet Opie hopkins, Netta Lee, Seven Pines Posted in: Women in History