“Your Place Is Here” – Clara Barton at the Battle of Fredericksburg

As Clara Barton gazed out over a darkened landscape in the early morning hours of December 11, 1862, her sleeplessness gave her a view of a wide river, with a town on the opposite shore glowing in the soft haze of the moon.

“It is the night before a battle,” she wrote in a letter to her cousin Elvira, “The enemy, Fredericksburg, and its mighty entrenchments lie before us, the river between – at tomorrow’s dawn our troops will assay to cross, and the guns of the enemy will sweep those frail bridges at every breath.”

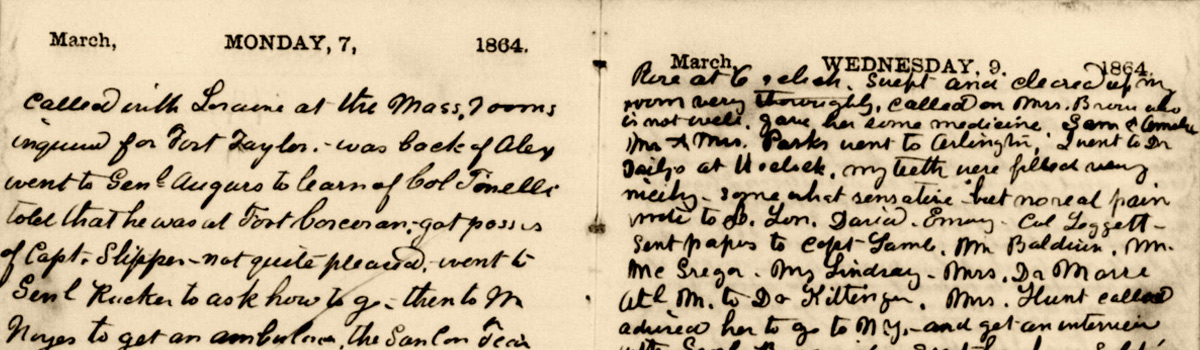

The 40-year-old war relief worker had been sporadically with the Army of the Potomac since its bloody fight at Antietam on September 17, 1862. She fell into routine in that autumn of discontent, when the most newsworthy army saw its famed commander fired by the Lincoln administration, and the appointment of a new, underwhelming commander. Barton gathered supplies in Washington and when her larders were full, she obtained a pass to distribute them to Union soldiers in the field.

In November, the Army of the Potomac arrived at Fredericksburg, Virginia with designs on cutting off a Confederate army from its capital at Richmond. However, circumstances led to delays that forced a direct confrontation at Fredericksburg itself. As the days passed into December, certainty that a major engagement was to occur along the Rappahannock River took hold in Washington. On 7th Street, Clara Barton emerged from her boardinghouse and set out for Fredericksburg, accompanied by a friend named Cornelius Welles.

She arrived at Falmouth on the banks of the Rappahannock and took up lodgings at the Lacy House, a large plantation overlooking the spires of Fredericksburg. It was from the veranda overlooking Fredericksburg that she watched a great drama take place on December 11, 1862. The Union Army, now armed with pontoon bridges to cross the frigid river, began preparing to force their way across the Rappahannock. They were repelled by heavy fire from Confederate soldiers barricaded in Fredericksburg’s buildings. When the crossing failed, orders came to the artillery stationed in the vicinity of Barton’s location at the Lacy House, on a rise of ground called Stafford Heights, to shell the Rebel-controlled town. A storm of explosive shells tore the vulnerable city to pieces as Barton looked on from the Lacy House.

She was soon pulled away from the horrible sight by an influx of wounded soldiers struck down during the fight. She staunched bleeding and looked after those who were being brought into the Lacy House, which had already been prepared as a field hospitalin advance of the fighting. A note from a surgeon, who had successfully crossed the river into Fredericksburg later on December 11, called for her to help. “Your place is here,” wrote J. Clarence Cutter, a surgeon with the 21st Massachusetts. And so Barton crossed the pontoon bridges and entered the destroyed community of Fredericksburg to assist the wounded for the rest of the day.

After a day of relative inactivity, December 13th dawned as a day of battle. Union forces began moving southward toward Confederate lines perched on hilltops south of Fredericksburg. Thousands of men poured onto the field and were cut down by Confederates who controlled the high ground, overlooking open fields. It was a one-sided slaughter. On December 13, the Army of the Potomac suffered a staggering 13,000 casualties – the Confederates only 5,000.

In the stricken city itself, Barton worked alongside Dr. Cutter in the field hospitals as grievously wounded men streamed in from the battlefield in front of Marye’s Heights. An officer passed into the city after the sun set on the horrific day and saw Barton tending to more than 50 “almost frozen” wounded soldiers who had been recovered from the battlefield by Dr. Jonathan Letterman’s ambulance workers.

Barton took time to write down the challenges the medical professionals faced in these ghastly surroundings:

Dr. Hitchcock most strongly and earnestly and indignantly remonstrates against any more removal of broken or amputated limbs, he declares it little more than murder, and says the greater proportion of them will die if not better fed and attended more room and better air.

The surgeons do all they can but no provision has been made for such a wholesale slaughter on the part of anyone, and I believe it would be impossible to comprehend the magnitude of the necessity without witnessing it.

Barton biographer Elizabeth Brown Pryor summed up Barton’s experience in Fredericksburg during and after the battle on December 13, 1862: “Barton was everywhere in that pinched and unhappy town, saw every wretched collection of wounded men, knew every ugly corner.”

Two days later, on December 15, the Army of the Potomac retreated back across the Rappahannock River in utter ruins. Clara Barton accompanied the troops crossing the pontoon bridges and returned once more to the Lacy House. The building had been utterly transformed.

All around the palatial home, wounded soldiers were lying in agony awaiting a surgeon’s care. “I have the house full, men lie on the floors as close as they can be stowed, a little straw here and there; the best we can do for them,” wrote Surgeon J. Franklin Dyer of the Lacy House.

The Lacy House where Barton worked tirelessly during and after the battle.

Barton wrote of similar chaos in the Lacy House as it took in almost 300 patients in the days after the retreat from Fredericksburg: “they covered every foot of the floors and porticos… lay on the stair landing…A man who could find opportunity to lie between the legs of a table thought himself rich [as] he was not likely to be stepped on.”

Barton remained at the Lacy House until all the patients were removed and sent on to larger medical facilities further north. She finally headed home to Washington, arriving there on December 31, 1862.

Only on her return home did the full weight of her experience at Fredericksburg strike her. It hit her like a hammer. She recalled those emotional moments in a letter written to Annie Childs in the spring of 1863:

I remember, four long months ago – one cold dreary, windy day, I dragged me out from a chilly street car that had found me ankle deep in the mud of the 6th Street Wharf and up the slippery street and my long flights of stairs into a room, cheerless, in confusion, and alone, looking in most respects as I had left it some months before…

The fires of Fredericksburg still blazed before my eyes, and her cannon still thundered in my ear, while away down in the depths of my heart I was smothering the groans and treasuring the prayers of her dead and dying heroes – worn, weak, and heart sick, I was home from Fredericksburg; and when, there, for the first time I looked at myself, shoeless, gloveless, ragged and bloodstained, a new sense of desolation and pity, and sympathy and weariness all blended swept over me with irresistible force, and perfectly overpowered, I sank down… and wept as I had never done since the soft hazy winter night that saw our attacking guns silently stealing their approach to the river, ready at the dawn to ring out the shout of death to the waiting thousands at their wheels.

Notes

Want to learn more about Clara Barton and her role in the Civil War? Check out these biographies of Barton:

A Woman of Valor: Clara Barton and the Civil War by Stephen B. Oates

Clara Barton: Professional Angel by Elizabeth Brown Pryor

And not everyone thought so highly of Clara Barton. Here’s an account of Union surgeon who didn’t particularly like Barton’s work at the Lacy House.

Speaking of the Lacy House (also known as Chatham), you can walk in the footsteps of Clara Barton by visiting the building today. It houses the headquarters of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

About the Author

Jake Wynn is the Program Coordinator at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

Tags: Burnside, Clara Barton, Fredericksburg, Lacy House Posted in: Uncategorized