Students Digitally Map Washington DC Refugee Camps

In antebellum Washington, D.C., an active slave trade flourished until 1850 and slavery itself persisted until 1862. Yet during the U.S. Civil War, tens of thousands of African American men, women, and children fled slavery and made their way to Washington in search of freedom for themselves, their families, and their communities.

In the fall of 2019, students taking History 396 at Georgetown University embarked on their own search for the stories of Washington’s wartime freedom-seekers. Together they created “Escaping Slavery, Building Diverse Communities: Stories of the Search for Freedom in the Capital Region Since the Civil War,” which is a publicly accessible digital history project recounting where formerly enslaved people went when they got to the capital region, what they encountered upon their arrival, and how they changed their own lives as well as those of the city, the region, and the nation.

The nineteen students who filed in for the first day of class just before Labor Day in 2019 were not quite sure what to expect when I told them to get ready for some Hands on History. In most of their history classes, they learned something about the past, and I certainly hoped that they would in this class as well.

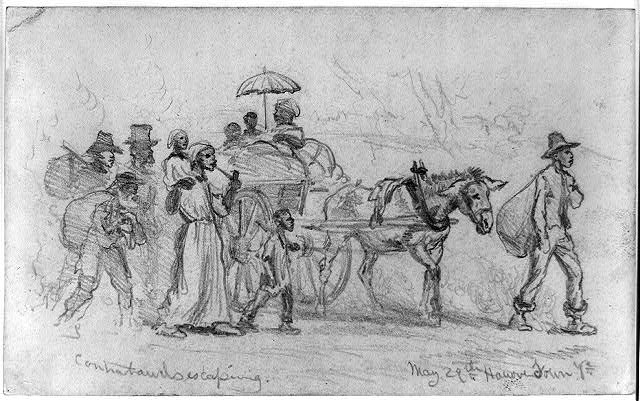

They would learn, for example, about the “contraband camp” phenomenon during the Civil War, which began thanks to the initiative of three men—Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend—who lived near Hampton, Virginia. These three enslaved men refused to be separated from their families by their owners’ plans to send them away to work on Confederate army fortifications. In May 1861, they ran to the U.S. Army installation at near-by Fort Monroe, Virginia. When their owner prevailed upon Union General Benjamin Butler to return the men in accordance with the Fugitive Slave Act, Butler turned slaveholders’ insistence on slaves as property against them: the universally recognized rules of war allowed the confiscation of enemy property in wartime, so Butler would retain the men as “contraband of war” rather than return them.

Word of the refuge the men found at Fort Monroe spread fast. Within weeks, hundreds of men, women, and children had joined them at Fort Monroe. In no time, men, women, and children fled slavery to wherever the Union Army could be found. Before the war was over, more than 400,000 freedom seekers would spend time in the “contraband camps” whose name came from Butler’s original play on words in May 1861. Thousands came to Washington, DC and Union-held portions of Northern Virginia like Alexandria. Students would learn something about them in History 396.

But chiefly what the class would teach, I emphasized, was how to be a historian. Being a historian, I told them, meant starting with questions and embarking on a search with no guarantee that they would find what they were looking for, or anything at all. It meant living with uncertainty and messiness and frustrating days when their labors turned up empty. But if we were lucky, it would also mean unexpected discoveries that challenged us to think about the Civil War and emancipation differently, and even changed how we viewed the city around us.

First, we took to the streets. Taking advantage of late summer’s long evenings, we headed to Logan Circle and walked the streets that once housed Camp Barker, one of Washington’s temporary wartime contraband camps where nearly 4,000 former slaves sought freedom. Today, Garrison Elementary School occupies that site, framed by a bronze and charred wood memorial to the contraband camp of long ago. We visited the African American Civil War Museum nearby on Vermont Avenue. We walked through the U Street district, noting the relationship of all these places to one another, and remembering that our evening stroll was only a beginning.

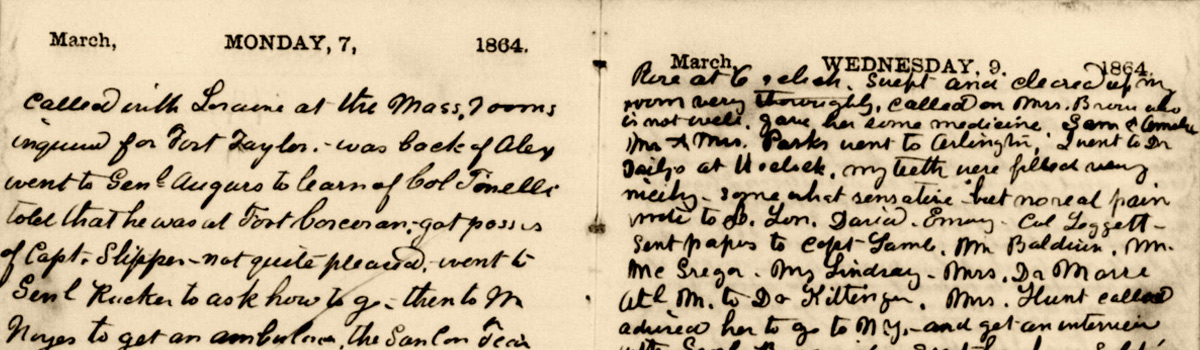

Then we got to work! Students each selected neighborhoods where Civil War refugees from slavery or their descendants made homes. Some students worked on Camp Barker and nearby locales, while others branched out to places like Howard University, Alexandria and Arlington, Virginia, the Barry Farm neighborhood, and more. They scoured old newspapers, official correspondence of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Union Army, court testimony, church records, city maps and directories, and genealogical records. They sifted through archival boxes, examined digitized documents, scrolled through (to them) ancient microfilm readers, and attended community advocacy meetings.

They found a multiplicity of stories and a variety of experiences united by a common—and ongoing—theme: the struggle to define what freedom means and to make it real in the face of daunting structural obstacles. Some of the formerly enslaved achieved liberation. Others faced disease, high mortality rates, racism, and the risk of re-enslavement. After the war, some founded schools and businesses. Others encountered bitter disappointment and betrayal. Their interwoven stories continue to make up much of the fabric of Washington today.

To tell these complex and interconnected stories, each student created a digital story map of their chosen neighborhood. We then compiled them into one collective story map, bolstered and stitched together with some additional work by me. The map is now live, and was even featured on the Organization of American Historians’ Featured Projects page. Please visit it, and through it, the many communities created by freedom-seekers past and present.

We all realize that many more stories exist beyond those that one class could uncover in one semester. We hope that “Escaping Slavery, Building Diverse Communities: Stories of the Search for Freedom in the Capital Region Since the Civil War” will inspire viewers to dive into their own research and uncover more stories of their own.

Learn more in this interview with Dr. Chandra Manning, the post’s author:

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Dr. Chandra Manning is an accomplished historian and author of Troubled Refuge and When this Cruel War Was Over. She graduated summa cum laude from Mount Holyoke College in 1993 and received the M.Phil from the National University of Ireland, Galway, in 1995. She took her Ph.D. at Harvard in 2002. Manning has taught history at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington, and currently is a Professor of History at Georgetown University.

Tags: Chandra Manning, Digital History, Freedom, Refugees, Washington DC Posted in: Wartime Washginton