“A Sacred Offering of Childhood:” Children and the United States Sanitary Commission

Museum members support scholarship like this.

“Dear Soldiers, …little girls…send this box to you. They hear that thirteen thousand of you are sick, and have been wounded in battle. They are very sorry, and want to do something for you. They cannot do much, for they are all small; but they have bought with their own money, and made what is in here. They hope it will do some good, and that you will get well and come home.”[1]

Mary Livermore discovered this note in a carefully packed box of handmade shirts, towels, handkerchiefs, and dried fruit while working in the packing room of the Northwestern branch of the United States Sanitary Commission. In almost every box of donations that she sifted through, she found similar notes from the item’s makers, but none were as touching as those from children. These “sacred offering[s] of childhood,” as she called them, reflected the sincere wish of children to contribute to the war effort. Likely encouraged and guided by their mothers, the girls that put together this box clearly wanted to provide aid and support to sick and wounded soldiers through their handmade clothing and personal items.

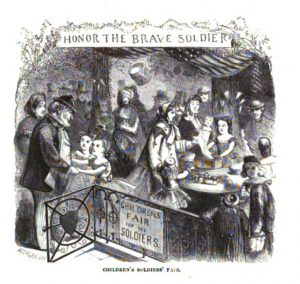

“Children’s Soldiers’ Fair.” From Frank B. Goodrich The Tribute Book: A Record of the Munificence, Self-Sacrifice and Patriotism of the American People during the War for the Union.

During the war, children across the North created clothing and bandages, donated money and other items, and participated in fundraisers to help soldiers in need. The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC), with its expansive and organized infrastructure, provided the repository for children’s patriotic donations. Northern women, engaged in their own work to aid soldiers, encouraged children to work alongside them. Through this work, children learned the valuable character traits of compassion and sacrifice for the sake of others. Perhaps more significantly, however, this positive and patriotic work, allowed children to experience the war in a favorable light. By actively contributing to the war, children could feel some measure of control over the tumultuous events in their everyday lives. While they may not have been able to control the circumstances that took away their fathers or older brothers, they could find solace in the fact that their saved pennies or pile of bandages might help a wounded soldier convalescing in a hospital far away.

At the outbreak of war, many northern children, both boys and girls, were tasked with scraping lint and rolling bandages. Both jobs were simple and mundane enough for young children to complete at the foot of their mothers busy with sewing clothing and bedding. The little workers created lint, used to pack wounds, by scraping at pieces of linen with knives. They tore up old bedding and clothing into long strips to be used for bandages. After the war, Clara Clough Lenroot, five years old in 1861, remembered going to the local church at the beginning of the war to scrape lint while her mother sewed with the other women. With her lint board and sharp pen knife, Clara scraped away at old pieces of household linens. “Very important we children felt,” she recalled, “as we scraped away the linen, making fluffy piles of the soft lint for the soldiers. That thought thrilled our hearts.” For Clara, and other children engaged in similar work—with fantastic imaginations and their thoughts to entertain them while working—the idea of their piles of lint and bandages saving a soldier’s life was exciting.[2]

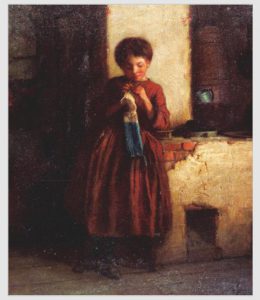

Eastman Johnson. Knitting for the Soldiers. 1861. New-York Historical Society.

In addition to creating lint and bandages, young girls also created articles of clothing and bedding for soldiers. Knitting socks or sewing shirts were two popular tasks suited to sewers still honing their needlework skills. A young knitter pinned a note to the pair of wool socks she made, writing, “these stockings were knit by a little girl five years old, and she is going to knit some more, for mother says it will help some poor soldier.” This girl was clearly motivated by the thought that her contribution would help a soldier in need. The note also reveals that this girl’s mother was the driving influence that encouraged her to pick up her knitting needles.[3]

In addition to making textile-based objects for soldiers, children donated saved money and other beloved items to soldier’s aid societies. Mary Livermore received a letter from two nine-year old girls wishing to send five dollars to the USSC that they earned together. They wrote that they desperately wanted to help the “poor sick soldiers” with their money. In Massachusetts, a younger sister of Caroline Hewins donated her beloved two-volume set of Grimm’s fairy tales hoping to comfort soldiers in the hospital. Caroline described her sister’s contribution as, “the dearest thing she could give her country.” This young girl, too young to sew or raise money, recognized the joy the books gave her and wanted to give soldiers something to raise their spirits while convalescing. Children during the war willingly gave away their money or favorite possessions, confident that their sacrifice would serve an important purpose in aiding soldiers.[4]

The USSC provided a reliable repository for children’s donations, as well as coordinated several successful fairs that channeled the fundraising efforts of children. During the war, the USSC held multi-day fairs in large cities such as Chicago, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, and New York. At these events, children, under their parent’s guidance and supervision, set up their own booths to sell goods to visitors. They also performed in tableaux and plays that charged an admittance fee. At the Metropolitan Fair in New York, held during April 1864, a single performance of Cinderella, starring John C. Fremont’s son Francis Preston as the Prince, earned $2,500. During the summer of 1863, the children of Chicago organized a series of children’s fairs on behalf of the USSC. These fairs were planned and run by children, ages nine through sixteen, with minimal help from adults. Held on the lawns or in the parlors of their parents, the children sold assorted goods from cushions and patriotic bookmarks, to dolls and confections. In two weeks the fairs netted over three-hundred dollars, all of which went to the USSC. [5]

“The Metropolitan Fair-The Children’s Department, Union Square.” 1864. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

In 1865, Alfred L. Sewell, a Chicago publisher, devised perhaps the largest and most lucrative money-raising effort by children during the war. The Army of the American Eagle fundraiser had children selling images of Old Abe the War Eagle, the mascot of the 8th Wisconsin for ten cents an image. After their first sale, the child became a private in the Army of the American Eagle. After that, they could raise their rank through the sale of more images. One dollar’s worth made them a corporal, ten dollars a captain, and so on, with four-hundred earning the child the rank of major-general. Sewell’s scheme proved immensely popular as over 12,000 children joined the ranks of the Army of the American Eagle, and raised over $16,000 for the Northwestern Sanitary Fair held from late April to June 1865.[6]

Northern children’s fundraising efforts and donations to the USSC highlight the active roles they assumed during the Civil War. Limited by their age and guided by their mothers, children found suitable ways to contribute to the war effort. Encouraged by the idea of cheering soldiers—just like their fathers or brothers—in hospitals made their sacrifices and hard work worthwhile.

End Notes

[1] Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War: A Woman’s Narrative of Four Years Personal Experience as a Nurse in the Union Army (Hartford, CT: A.D. Worthington & Co., 1889) 137.

[2] Clara Clough Lenroot, Long, Long Ago (Appleton, WI: Badger Printing CO., 1929) 14.

[3] Frank B. Goodrich, The Tribute Book: A Record of the Munificence, Self-Sacrifice and Patriotism of the American People during the War for the Union (New York: Derby & Miller, 1865) 153.

[4] Livermore, My Story, 165; Caroline M. Hewins, A Mid-Century Child and Her Books (New York: The MacMillian Company, 1926) 65.

[5] James Marten, The Children’s Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000) 177-181; Livermore, My Story, 152-154.

[6] Livermore, My Story, 627.

About the Author

Kristen Hunter is a graduate student at George Mason University studying the History of Decorative Arts. She is currently completing her Master’s thesis, “By Her Needle and Thread,” which looks at how women used material objects of their production to shape their families’ experiences of the Civil War. She also holds a BA in History from Villanova University.

Tags: Chrildren, civil war medicine, Mary Livermore, United States Sanitary Commission, USSC Posted in: Uncategorized