Clara Barton and the Medical Disaster of First Bull Run

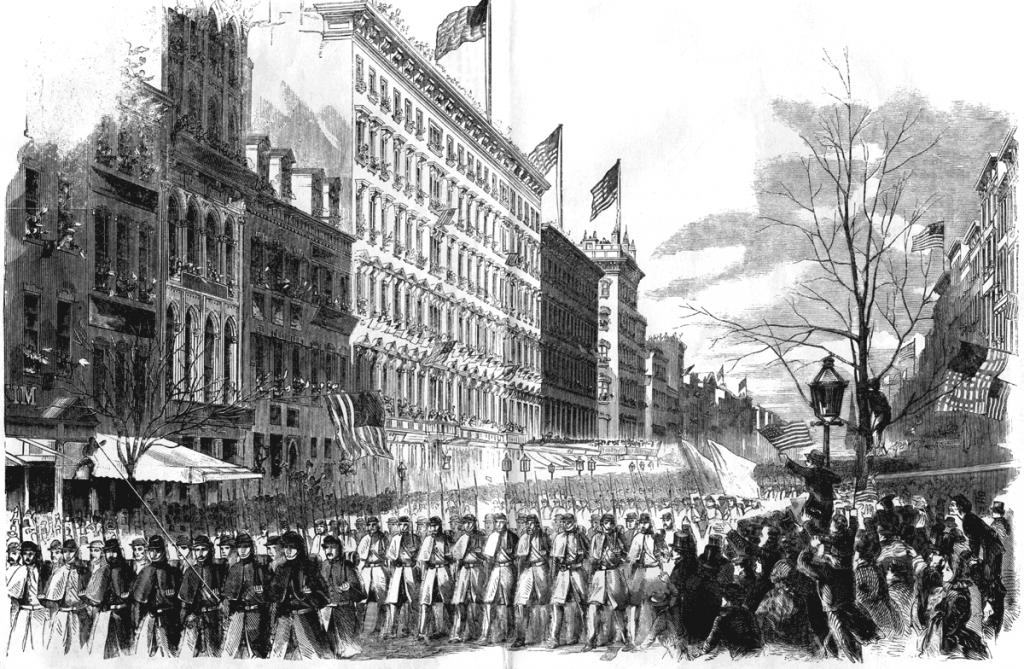

On July 16, 1861, Clara Barton watched more than 30,000 “noble, gallant, [and] handsome” Federal soldiers, “armed to the teeth,” march out of Washington to confront a Confederate army near Manassas Junction. The atmosphere was celebratory and jubilant.

When those same soldiers came running back to the Union capital less than a week later after being routed at the Battle of Bull Run, the mood in the city became much darker. The medical disaster that followed inspired Clara Barton to bring supplies to the front lines and the US Army to change how they approached battlefield medicine.

Harpers Weekly sketch of Union soldiers heading to Washington. The atmosphere shown here mirrored the scene where the Union army left Washington for Bull Run.

Many around the country, soldiers and citizens alike, naively expected a short conflict with no need to prepare for large numbers of wounded. In the days before the First Battle of Bull Run, as the US Army neared contact with the enemy, the army’s medical department made no preparation to set up hospital sites until after the battle began.

Before the army left Washington, military authorities ordered all sick and infirm men to remain behind in the city’s improvised hospitals. No permanent military hospital sites had been established in the city. Instead, sick soldiers were languishing in abandoned warehouses, churches, schools, and other public buildings. That meant Washington’s “hospitals” were already overflowing when the army left for battle. There was simply no space for more patients in these makeshift facilities.

On July 18, there was a preliminary skirmish fought at Blackburn’s Ford that resulted in about 100 combined casualties. The engagement was tiny by later Civil War standards, but when it happened, it was a major battle that nearly overwhelmed the Union army’s medical stores in the field.

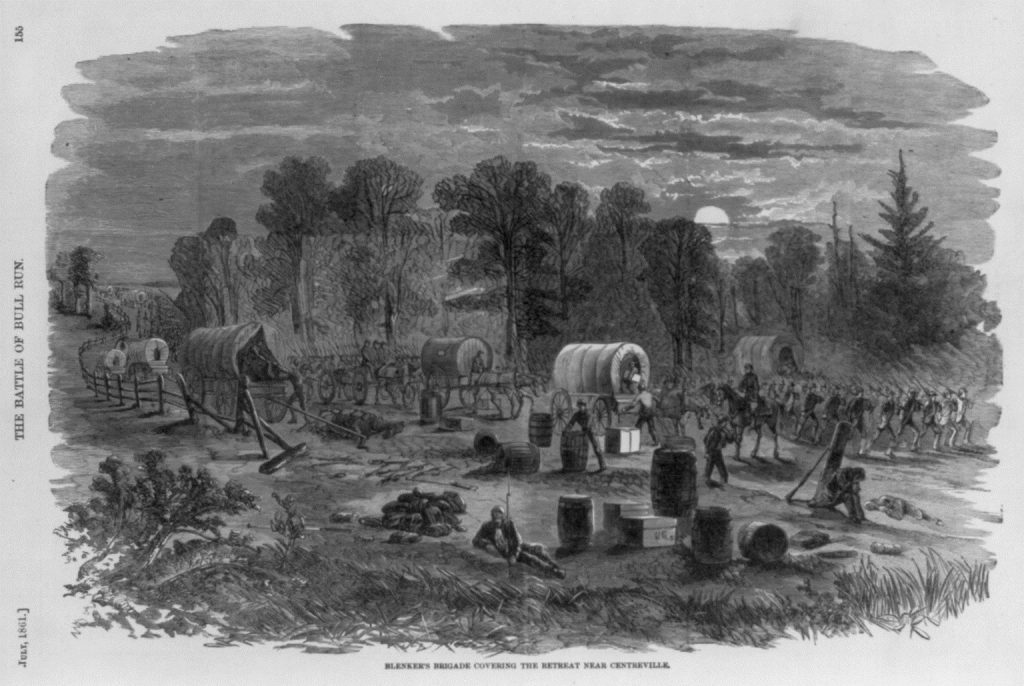

At the Union army’s staging point near Centreville, Medical Director William King made no efforts to pre-stage hospitals before the fight at Blackburn’s Ford. Only when he met ambulances bringing in the wounded from the skirmish did he “select suitable buildings for hospital purposes.”[1] After King and his subordinates selected a building for hospital use, the wagon train of wounded was ordered to wait while 12,000 soldiers passed, blocking their path to the field hospital. A further breakdown in functionality occurred when one regimental surgeon refused to treat the wounded from another regiment. All this did not bode well when, three days later, the number of injured would increase from 100 wounded men to more than 1,100.

Photograph of the Stone

Church in Centreville used as a hospital after Blackburn’s Ford. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861 resulted in a resounding Union defeat. The entire Union army fled the 30 miles back to Washington, creating a scene Clara Barton described as “sad, painful, and mortifying.” The walking wounded led the way rather than remain in field hospitals closer to the battlefield and risk Confederate capture.

The two largest hospital centers in Washington were the E Street Infirmary (which treated about 200 patients per year before the war) and the Union Hotel Hospital in Georgetown, a makeshift facility that had a staff of one surgeon and six unpaid nurses. When those sites filled quickly, the army frantically searched for other options. Hotels, churches, schools, and even some private homes were seized to provide space for the injured.

Newspaper image of the retreat from Bull Run. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Wounded men were also sent to the U.S. Patent Office – where Clara Barton worked – to recover in the building’s famed exhibition hall. When she wasn’t working, Barton spent her time with wounded soldiers. She distributed food, clothing, and other necessities to the patients. She sat with them for hours writing letters, feeding disabled men, and talking with them to pass the time. The experience solidified her resolve to gather supplies and distribute them among Federal soldiers.

In caring for the soldiers in the temporary hospital, she began to wonder about possibly expanding her efforts from Washington to the battlefields surrounding the city. Might she accomplish more near the scenes of carnage and destruction? Her instincts were borne out by events that followed over the subsequent four years – Barton was to play an important role on the battlefield.

While the medical department scrambled to care for the wounded pouring into Washington, few efforts were made to head back to Manassas to collect the wounded Union soldiers left behind during the retreat.

A significant number of Union wounded were left on the battlefield because the medical department didn’t have authority over most of the ambulances. The majority of the army’s ambulances belonged to quartermaster department. Without access to those ambulances, the medical department hired local farmers to use their wagons. When the shooting started, they promptly fled, leaving Union surgeons with no effective way to retrieve the wounded.

A New York Times editorial published on July 27, 1861 (six days after the battle) excoriated the poor efforts to care for the wounded men of the US Army: “We are all inexpressibly pained to learn…that very inadequate provisions had been made by the regular authorities, for the proper care of the wounded in that late battle. It seems incredible…that some of our gallant soldiers for sheer want of hospital garments, [are] even yet sweltering in their bloody uniforms, festering with fever and maddened with thirst.”[2]

Barton drew inspiration from these terrible circumstances and took action. She began actively soliciting people from across the North for food and medical supplies to support her relief efforts. Her plea was based on personal experiences with the wounded from Bull Run. “It is said, upon proper authority, that ‘our army is supplied’… how this can be so, I fail to see,” she wrote.[3]

Over the subsequent months, friends, family, and affected citizens sent Barton an overwhelming amount of supplies, completely filling her small boardinghouse in Washington. Her trove of supplies eventually grew to fill three additional warehouses in the Union capital.

The medical disaster at Bull Run in July 1861 convinced Clara Barton, ordinary citizens, and even the Union medical department to take the medical needs of the US Army in the aftermath of a battle more seriously. It was a moment that changed battlefield medicine and the life of Clara Barton forever.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

Endnotes

[1] Quoted from Ira M. Rutkow, Bleeding Blue and Gray: Civil War Surgery and the Evolution of American Medicine (New York: Random House, 2005), p 19.

[2] Quoted from Alfred Bollet, Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs (Tucson: Galen Press, 2002), p 2-3.

[3] Quoted from Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Clara Barton: Professional Angel (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1987), p 81.

Bibliography

Alfred Bollet. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson: Galen Press, 2002.

Stephen B. Oates. A Woman of Valor: Clara Barton and the Civil War. New York: The Free Press, 1994.

Elizabeth Brown Pryor. Clara Barton: Professional Angel. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1987.

Ira M. Rutkow. Bleeding Blue and Gray: Civil War Surgery and the Evolution of American Medicine

Kenneth J. Winkle. Lincoln’s Citadel: The Civil War in Washington, DC. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

About the Author

John Lustrea is a member of the Education Department and the Website Manager at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He earned his Master’s degree in Public History from the University of South Carolina. Lustrea has previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park during the summers of 2013-2016.

Tags: Blackburn's Ford, Civil War, Civil War hospitals, civil war medicine, Clara Barton, First Bull Run, medical department, Washington DC, William King Posted in: Uncategorized