“Senses Were Benumbed:” How a Civil War Nurse Handled Trauma

Cornelia Hancock, a twenty-four-year-old Quaker woman, arrived at the Gettysburg battlefield on July 6, 1863.[1] She was there against the wishes of Army nurse superintendent Dorothea Dix due to her “youth and rosy cheeks.” Hancock would not stop volunteering her aid for the next two years, and her tireless assistance at the front lines earned the respect of soldiers and doctors alike. In her years as a nurse, Hancock volunteered following the Battle of Gettysburg, the Battle of the Wilderness, at understaffed contraband hospitals, during the battle of Fort Stevens, and at the Siege of Petersburg.

Cornelia Hancock

Hancock acted independently and never joined organizations such as the U.S. Sanitary Commission or the U.S. Army, yet both organizations seldom denied her access or supplies. Though she helped countless soldiers and often wrote home about her joy in having something useful to do, one does not experience such violent and gruesome sights and continue unchanged. To survive on the front lines, Hancock found herself hardening both her emotions and behaviors in the face of these traumatic events.

Fascinating histories have been written about soldiers, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder, yet few acknowledge that women who did not fight could still experience war’s impact on mental health, particularly when nursing at the front.[2] A close reading of Cornelia Hancock’s letters reveals that she was similarly affected by the consequences of war. When she arrived at Gettysburg, the “sickening, overpowering, awful stench” of “swollen and disfigured” unburied soldiers greeted Hancock. The groans from the wounded soldiers on the amputating table haunted Hancock, a place which “literally ran blood” for seven days. The hot sun provided no respite for the soldiers, and the air was “rent with petitions to deliver them from their suffering.”[3] Only the Battle of the Wilderness could compare to Gettysburg in her recollections. It was there Hancock spent two weeks in the “scorching sun” nursing soldiers whose wounds “had not been opened for 36 hours.”[4]

Cornelia Hancock at Brandy Station, surrounded by soldiers. Courtesy of Library of Congress

Cornelia Hancock found that her “senses were benumbed” by her experiences on the front.[5] After Gettysburg, she told her sister “I feel assured I shall never feel horrified at anything that may happen to me hereafter.”[6] “You will think it is a short time for me to get used to things,” she reaffirmed, “but it seems to me as if all my past life was a myth.”[7] Even the “screams of agony” did not “make an impression” on the now-battle-weary nurse, and Hancock even claimed that “I could stand by and see a man’s head taken off” due to her intense exposure to the grisly sights of Gettysburg’s aftermath.[8]

This necessary numbness could sometimes make her callous, as she wrote that “It does not appear to me as if one death is anything to me now” in response to news of her neighbor’s death.[9] Yet becoming “used to the suffering” could also bring happiness. Sometimes even in the face of death she and the other nurses and doctors could be “very jolly” and “have a good time.”[10]

In addition to her mental fortitude, Hancock found herself becoming rougher around the edges in other ways. Her letters home to the Quaker community in Salem County, New Jersey reveal her neighbors worries about Cornelia’s improper activities on the front, such as living alone and horseback riding. After responding many times to these concerns, Hancock finally wrote agitatedly that those complaining “cannot expect everyone to be satisfied to live in as small a circle as themselves in these days of great events.”[11]

Hancock also shocked her family when she wrote that “Everybody swears here, if I do when I get home you need not be surprised.”[12] As Hancock spent more and more time in the male environment of the battlefield, she found herself increasingly participating in non-“ladylike” activities, and felt no concern in doing so. “A soldier’s life is very hardening,” wrote Cornelia, when she boasted of having a tooth pulled without flinching.[13] She clearly considered herself a part of that rough life.

Those experiences did not mean that the deeper meaning of death was completely lost on Cornelia after months of nursing. Though she became numb to the death of soldiers and others, the deaths of those she knew affected her deeply. Hancock wrote home often about the fate of one Captain Dod, with whom she had formed a friendship during his time as a hospital patient. Captain Dod died with his mother at his side, which made his “deathbed just like a home deathbed.”[14] This peaceful and “Christian” death of a “splendid looking officer” was a “very affecting” scene for Hancock, and she requested that her mother both preserve her letter and mark the date of Dod’s death.[15] In order for Hancock to steel her heart against suffering, she had to prevent herself from forming a deep connection with the wounded. Her close connection to Captain Dod, therefore, caused her to mourn his passing more than others.

Though Cornelia Hancock wrote home often about the horrors of war, these experiences did not outweigh her sense of fulfillment in doing her duty as a nurse. After the war, she traveled to South Carolina to nurse newly emancipated African-Americans. Though Hancock did not describe any nightmares or lasting effects of the trauma of the Civil War, her wartime letters reveal that she hardened herself in order to cope with the suffering she encountered daily. Studying her letters, as well as the other writings of Civil War nurses, reveals that they too experienced trauma much like the soldiers, and helps add to historians’ understanding of the mental effects of wartime.

Endnotes

[1] Hancock, Cornelia, Letters of a Civil War Nurse: Cornelia Hancock, 1863-1865, Ed. Henrietta Stratton Jaquette (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998) 2

[2] See Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York: Knopf, 2008); Eric T. Dean, Jr., Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999); Earl J. Hess, The Union Soldier in Battle: Enduring the Ordeal of Combat (Lawrence, University Press of Kansas, 1997); Michael W. Schaefer, “’Really, Though, I’m Fine’: Civil War Veterans and the Psychological Aftereffects of Killing,” in The Civil War in Popular Culture: Memory and Meaning, ed. Lawrence A. Kreiser Jr. and Randal Allred (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014); Kathryn S. Meier, “No Place for the Sick: Nature’s War on Civil War Soldier Mental and Physical Health in the 1862 Peninsula and Shenandoah Valley Campaigns,” Journal of the Civil War Era 1.2 (June 2011)

[3] Hancock, 2

[4] Cornelia Hancock to Joanna Dickeson, July 18, 1864

[5] Hancock, Letters of a Civil War Nurse, 2

[6] Cornelia Hancock to Ellen Hancock Child, July 8, 1863

[7] Cornelia Hancock to Rachel Hancock, July 26, 1863

[8] Cornelia Hancock to Eliza W. Farnham, July 8, 1863

[9] Cornelia Hancock to Ellen Hancock Child, August 6, 1863

[10] Cornelia Hancock to Eliza W. Farnham, July 8, 1863

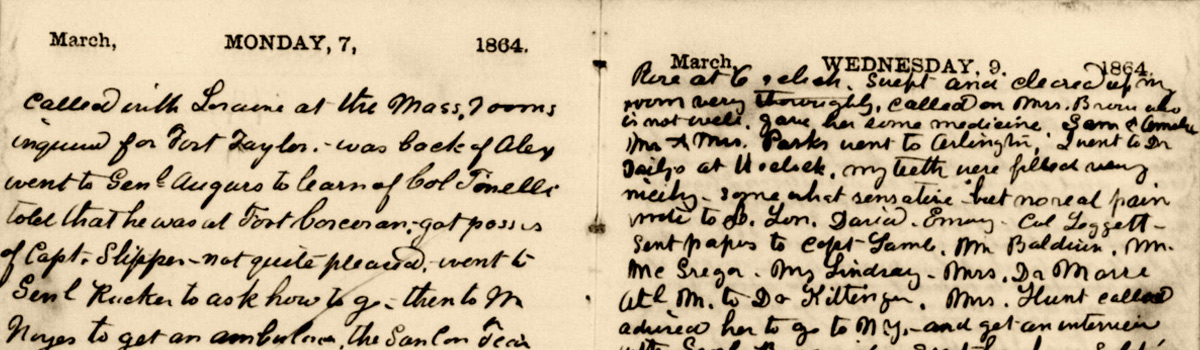

[11] Cornelia Hancock to Rachel Hancock, March 27, 1864

[12] Cornelia Hancock to “My Dear Sarah,” March 2, 1864

[13] Cornelia Hancock to Rachel Hancock, September 1863

[14] Cornelia Hancock to Ellen Hancock Child, August 27, 1864

[15] Cornelia Hancock to Rachel Hancock, August 27, 1864

About the Author

Melissa DeVelvis is a doctoral student in history at the University of South Carolina, specializing in the Civil War era, gender studies, and sensory and emotions history. She is currently processing and archiving the collection of Bishop John Hurst Adams for the South Caroliniana Library and is a part-time site interpreter for Historic Columbia.

Tags: Civil War hospitals, Civil War nurse, Cornelia Hancock, Gettysburg, Petersburg, Wilderness Posted in: Uncategorized