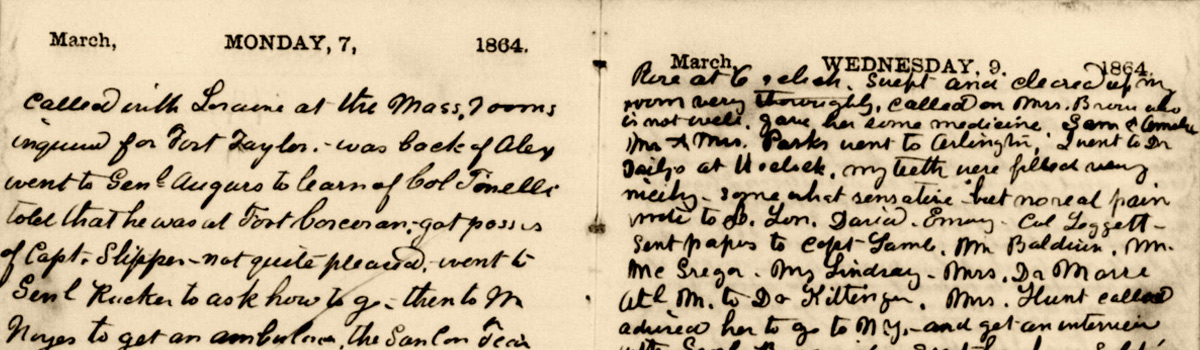

“The Fate of Your Loved Ones” – Dorence Atwater’s List

In 1866, a Civil War soldier and former prisoner-of-war named Dorence Atwater published a remarkable document in partnership with Clara Barton.

A List of the Union Soldiers Buried at Andersonville represented the conclusion of a saga for the Connecticut soldier that lasted more than three years and took him from the battlefields of the Civil War, to the conflict’s most infamous prison camp in Georgia, to Barton’s Missing Soldiers Office, with a stint in a New York state prison along the way.

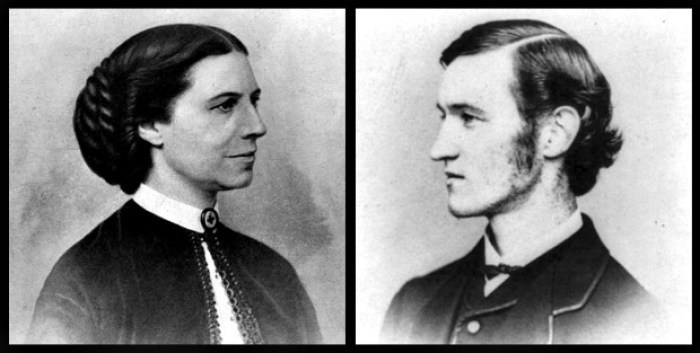

Clara Barton and Dorecne Atwater

Atwater served with the 2nd New York Cavalry during the Civil War and was captured by Confederate forces near Hagerstown, Maryland in early July 1863. His captors transported him to the Confederate capital, where he spent five months on Belle Island, a dot of land in the James River that was utilized as a prison camp for Union soldiers. While in Richmond, he assisted in accounting for supplies sent by the Union Army for the prisoners. In 1864, he was transferred to the prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia.

While there, he was paroled and sent to work in the office of Surgeon J.H. White as a clerk. His task: “keep the daily record of deaths of all Federal prisoners of war.”

The horrors he witnessed at Andersonville led him to begin keeping a secret copy of his register in August 1864, a list that he safely brought with him to Union lines in March 1865.

Over the subsequent months, these rolls served to make Atwater famous, but also became a source of seemingly unending difficulties. The War Department demanded the register that Atwater smuggled out of Andersonville which he eventually turned over. Atwater, however, desired to publish the register in order that the families of those who perished at the Confederate prison camp could learn of the fate of their loved ones.

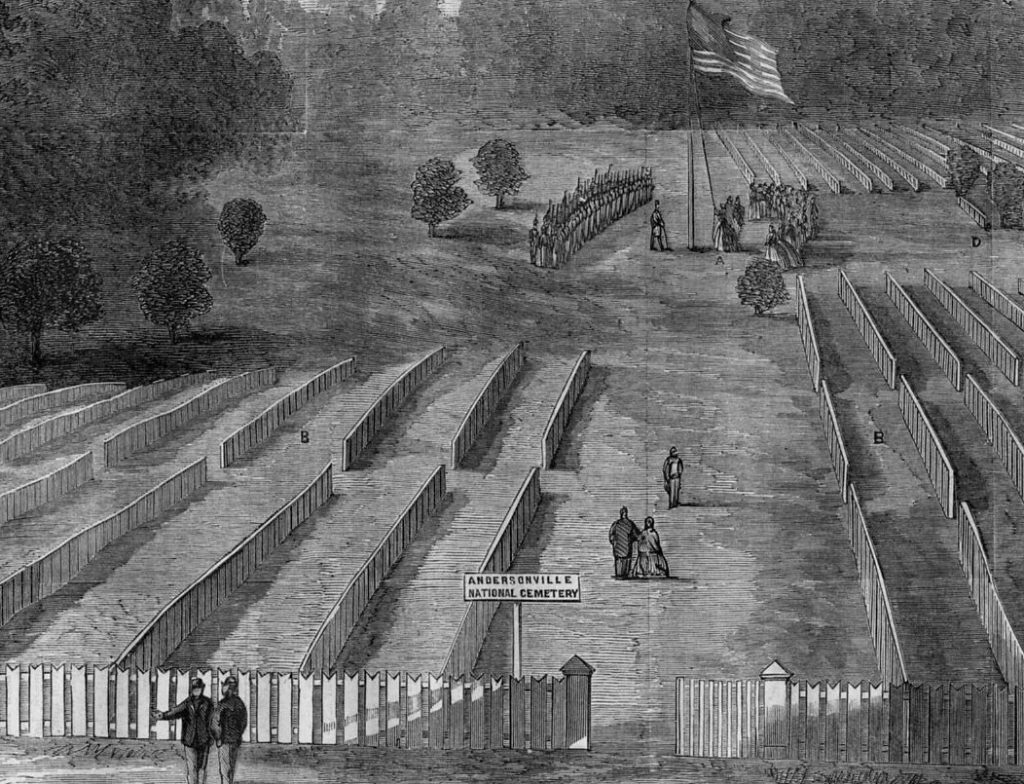

In the summer of 1865, Atwater connected with Clara Barton and together they accompanied an expedition to Andersonville in order to document the site and its horrors. They also assisted in identifying many of those buried in what became Andersonville National Cemetery.

Clara Barton raising the flag at Andersonville National Cemetery, as portrayed in Harpers Weekly.

While on the expedition, Atwater took back the register he had written while in the prison camp for the purpose of publishing the list. For this action, he was court-martialed and sentenced to 18 months in prison for larceny. It was always the War Department’s position that Atwater sought to make a profit by publishing the list. In September 1865, he arrived at Auburn State Prison to begin his sentence. After two months of hard labor, President Andrew Johnson pardoned Dorence Atwater and he again became a free man.

And what did he do upon gaining his freedom?

“I immediately set about preparing [the register] for publication, and have arranged to have it printed and placed within your reach at the cost of the labor of printing and material, having no means by which to defray these expenses myself,” he wrote.

By working together with Clara Barton, who also wrote a lengthy essay at the opening of the book, Atwater was able to publish the list of Andersonville victims through the Tribune Association of New York. The cost of the book: 25 cents.

Atwater’s journey made him into a public figure and his fame increased when he began traveling the lecture circuit with Clara Barton. Together, they told the story of Andersonville Prison and the efforts to identify those who went missing during the Civil War.

In the dedication for the book, Atwater addresses those who lost family members and friends at Andersonville. In it, he explains his motivations for publishing the list and for his work with the Missing Soldiers Office:

This Record was originally copied for you because I feared that neither you nor the Government of the United States would ever otherwise learn the fate of your loved ones whom I saw daily dying before me. I could do nothing for them, but I resolved that I would at least try to let you sometime know when and how they died. This at last I am now able to do.

About the Author

Jake Wynn is the Director of Interpretation at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

Tags: Andersonville, Andersonville National Cemetery, Clara Barton, Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office, Dorence Atwater Posted in: Uncategorized